Governments worldwide are diverse in structure, authority, and function. Understanding their classifications—monarchy, aristocracy, democracy, and republic—is crucial for analyzing political systems. This guide explores the forms, characteristics, and historical evolution of governments, highlighting how they exercise power and serve society.

“All governments are, in fact, carried on by a relatively small number of persons; yet the form they take defines how society is governed.” — Lord Bryce

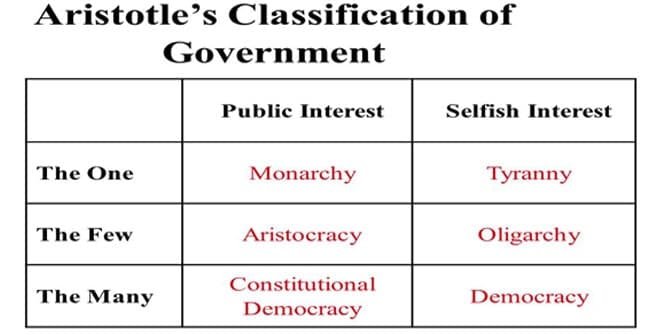

Classifications of government.

Identifying a form of government is also difficult because many political systems originate as socioeconomic movements and are then carried into governments by parties naming themselves after those movements, all with competing political ideologies. Experience with those movements in power, and the strong ties they may have to particular forms of government, can cause them to be considered as forms of government in themselves.

The State and Government Distinguished:-

From an examination of types of states and unions of states, we come now to consider the forms and kinds of gvernment,always keeping in mind that the state and its government are,strictly speaking, separate and distinct institutions.

The state, as we have seen, is a politically organized community of people independent of external control Or nearly so, and sovereign in respect to its internal affairs, or at least possessing so large an autonomy that for all practical purposes it may be regarded as a state. Government on the other hand, is the organization through which the state manifests it’s will, issues its commands, and conducts its affairs.

While, as pointed out in a previous article, all states are alike in their essence, that is, in respect to the component elements which enter into their make-up, and, in general, in respect to their ends and objects, and therefore do not readily lend themselves to differentiation and classification, governments, on the other hand, vary widely in respect to the form of their Organization, frequently in respect to their spirit and methods, in respect to the mode in which those who govern are chosen, the nature and extent of the authority with which they are invested, the particular objects which they seek to accomplish, the relations between their legislative, executive, and judicial organs and various other matters.

Attempts to classify them have usually, therefore, been more successful than attempts at the classification of states, for the reason that satisfactory criteria can be found upon which various governments can be grouped into one class and others in a different class in such a manner that the distinction between the different classes subserves both practical and scientific ends.

Criteria of Classification :-

As in the classification of states, the essential problems is to and the proper criteria. Naturally, the political scientist, the jurist, the international lawyer, and the sociologist, each frequently approaching the subject from a different point of view and each emphasizing different characteristics of governments, are not always in agreement as to what these criteria should be. Political scientists themselves are not in accord in respect to the tests which should be adopted.

Many classifications which have been proposed have not been satisfactory for various reasons: some of them because they were not based upon any consistent scientific principle others because the criterion adopted leads to classifications which are of little scientific or practical value.

One difficulty, it may be observed, lies in the fact that in recent times a great variety of new forms of government have come into existence and these are constantly undergoing changes which differentiate them fundamentally from the old forms out of which they evolved.

The result is that classifications made in one epoch and satisfactory enough at the time soon become out of date,

Monarchy :-

Adopting the same test that is employed in classifying states, namely, the number of persons in whom the supreme and final authority is vested, many writers, especially the older ones, have classified governments as monarchies, aristocratic, and democracies. In its widest sense any government in which the supreme and final authority is in the hands of a single person is a monarchy, without regard to the source of his election or the nature and duration of his tenure.

In this sense it is immaterial whether his office is conferred by election (by parliament or people) or is derived by hereditary succession, or whether he bears the title of emperor, king, czar, president, or dictator. It is the fact that the will is one man ultimately prevails in all matters of government which gives it the character of monarchy.

As pointed out in a previous chapter, however, some writers consider monarchy to be a form of government in which the chief of state derives his office through inheritance, according to rules of hereditary succession which in practice vary in different states. It is this characteristic which distinguishes a monarchy from a republic, the latter being a form of government in which the head of the state is elective.

Jellinek, as we have seen, defined monarchy as a government by a single physical will and he emphasized that its essential characteristic is the competence of the monarchy to “express the highest power of the state.” If he is merely a titular chief, his power being actually exercised by others, the government is in reality a republic, whatever may be the title of the chief of state, the source of his election, or the nature of his tenure.

Thus, he says, France under the constitution of 1791, although officially characterized as a monarchy, was in reality a republic With a here ditary chief of state The same might be said of the British monarchy.

Kinds of Monarchy :-

Considered from the standpoint of the source from which the monarch derives his office, monarchies may be classified as hereditary and elective, or they may be a combination of both. Most monarchies of the past and all of those, which now exist were and are hereditary in character that is, the monarch inherits the crown according to a fixed rule of succession, this may have been determined by the constitution or an act of parliament, or it may have been a rule of the particular dynastic house or family to which the monarch belonged, or it may have been determined partly by the one and partly by the other.

The rules have varied in different states. As already stated, instances of so called “elective” monarchies have not been Packing in the past. The early Roman kings were elective and so were those of the ancient monarchy of Poland. The emperors of the Holy Roman Empire were chosen by a small college of electors, usually from the same family.

During the Middle Ages elective monarchies were not uncommon, but they usually became hereditary in consequence of the practice of choosing the kings from a particular family. They were not always, however, chosen for life, a practice which Jellinek considered to be contrary to the nature of true monarchy.

In early times monarchs were originally chosen or in some form accepted by the people, though the hereditary feature was so strong that the elective principle was gradually pushed into the background. Speaking of the election of the early English kings, Stubbs observed that the king was in theory always elected and the fact of election was stated in the coronation service throughout the Middle Ages in accordance with the most ancient precedent.

But, he adds, it is not less true that the succession was by constitutional practice restricted to one family, and that the rule of hereditary succession was never except in great emergencies and in most trying times, set aside. In a sense, of course, the English monarchy is still elective, since parliament claims and exercises the right to regulate the law of succession at its pleasure.

In the case of several more recently created states, such as Belgium and Some of the Balkan states the first monarchs were chosen by election their successors inheriting their crowns by hereditary succession.

So the new king of Norway was elected by the Norwegian parliament in 1905, following a plebiscite which pronounced in his favor, but thereafter the crown will be transmitted by hereditary succession. In 1903, after the assassination of the king of Serbia, his successor was chosen by the Serbian parliament.

Absolute Monarchies :-

Considered from the standpoint of their character, monarchies have usually been classified as:

- Absolute, arbitrary, or despotic, and

- Constitutional, parliamentary, or limited.

An absolute monarchy is one in which the monarch is not merely the titular head of the state but is actually the sovereign, that is, his will is the law in respect to all matters ,upon which it is proclaimed. In short, he is bound by no will except his own.

Under such a system the state and the government, legally speaking, are identical, the monarch being not only an organ of government, and the sole organ, but also the sovereign. The nature of his power was expressed by the Roman maxim , quod principi placuit legis habet uigorem, and later by the French version of the same maxim qui veut le roi, si veut la loi. The boast attributed to Louis XIV, “ I am the State ” (l’état, c ’est moi) was a fairly accurate description of the role of a typical absolute monarch.

Examples of absolute monarchies were common in the Middle Ages and some of them Survived to a date well on in the nineteenth and even the twentieth century. Among them were the Russian and Ottoman monarchies, and to a less degree those of Prussia, Austria, and Hungary. With the advancing tide of democracy, however, absolute monarchy has completely disappeared from the continent of Europe. In form it still survives in a few more or less backward states of Asia and Africa.

Limited Monarchy :-

What is usually described as limited monarchy is one in which the power of the monarchy is restricted by the prescriptions of a written constitution or by certain unwritten fundamental constitutional principles, such as the British monarchy. These constitutional rules or principles define in some degree the powers of the monarch, or limit what is called the “royal prerogative” and usually upon his accession to the throne he is required to take a solemn oath to respect and observe them.

In some cases these constitutions, it is true, were not the work of national assemblies representing the people but were framed and promulgated by the monarch himself (e.g., the Prussian constitution of 1850 and the existing constitutions of Italy, 1848), but once promulgated it was understood that such of their prescriptions as placed limitations upon the rights and powers of the monarch were in the nature of a contract-between him and the people and therefore binding upon him.

All the surviving monarchies of Europe and some of those of Asia and Africa, fall within the class of limited monarchies. Those which belong to each class may be and have been subdivided into various types, but the lines o£demarcation which separate them are mainly distinctions of degree or of historical development, and little or nothing would be gained by dwelling upon them.

Aristocracy :-

Aristocracy is usually defined as a form of government in which political power is exercised by the few. Some writers, in the endeavor to be more exact, define it as government by a minority of the citizens. But as thus defined it is not necessarily government by a few, since the minority may be numerically a very large one, the line of demarcation between it and the majority may be so shadowy in fact that the distinction is not sufficient to distinguish the character of a government by the one from that of the other.

In fact, in many states regarded as democratic, political power is exercised by a minority of the citizens. Formerly, women had no voice or share in the government, and this is still true in some states. In all countries minors are disfranchised in some illiterate persons are excluded from voting and in some soldiers, convicted criminals, bankrupts, paupers, and other classes are debarred.

It would seem therefore, to be more exact to define aristocracy as a form of government in which only a relatively small proportion of the citizens have a voice in the choosing of public officials and in determining public policies. It is not practicable to lay down any precise rule as to the size of the minority which would make the government aristocratic in character. The ancient Greeks conceived aristocracy to be government by the best.

Whether they meant by the best those who were the most highly qualified by education, experience, and moral character or those who were superior to the rest by reason of their wealth or social status, is not clear. In either case it would normally be government by the few, though not necessarily so, since a condition of society is conceivable in which the best intellectually, morally, and economically would constitute a majority of the population.

The late Professor Jellinek, who considered aristocracy to be a special form of a more general type which he called republic, emphasized the social aspect of aristocracy. Aristocracy he conceived to be a form of government in which some particular class played the dominant role.

It might be a priestly, military, professional, or land owning class or several or all of those combined. In any case, they constitute a fraction of the population, juridically distinct from the mass, by reason of certain privileges or rights which they enjoyed. Aristocracy in all its forms, he said, rests upon the existence of a preponderant social element, which is independent as such of the state, and which, politically, exercises domination over the rest.

Aristocracy as a form of government was very common in former times. Many governments popularly described as monarchies were in reality aristocracies.

Jellinek recognized two general types:

first, those in which the ruling class was entirely separated from the rest of the population so that it was impossible for an individual who did not belong to the ruling class to gain admission to it.

second, those in which there was nothing of a juridical nature to prevent a member of an inferior class from acquiring under certain conditions political privileges reserved for the dominant class.

Examples of the first type were hereditary aristocracies, of the second type were those based upon wealth, education, social prominence, etc.

Rousseau, as is well known, classified aristocracies as natural, elective, and hereditary. By a natural aristocracy, he meant a government by those who by their natural ability as leaders, and by education and experience are best qualified to govern while by an elective aristocracy he meant a government by the relatively few who are chosen by the whole mass. The elected aristocrats might or might not be at the same time the natural aristocrats, depending upon the action of the electorate in making their choice.

Oligarchy :-

The ancient Greeks carefully distinguished between aristocracy and oligarchy. Aristotle defined the latter as a government by the few in their own interests, or more correctly, government by the wealthy, it was therefore a perverted form of aristocracy, which was government by the good or best people of the state.

The late Professor Seeley called it a “derangedr” or “diseased” form of aristocracy. Popular usage to-day however, rarely distinguishes between aristocracy and oligarchy, the two terms usually being employed indiscriminately to describe any government in which only a small minority have the controlling voice.

But a few writers still observe the distinction. Thus they say the government of Prussia was formerly an oligarchy rather than an aristocracy, but the difference hardly seems important. It was in fact a government in which the so~called junker land-owning aristocracy, together with the other wealthy and bureaucratically trained classes, exercised the controlling power.

Whether it was an oligarchy or an aristocracy is largely a matter of definition. This form of government, whether we call it aristocracy or oligarchy, in the sense of being government by a relatively small class, no longer survives in any European country, although, as Will be pointed out in a later chapter, the upper legislative chambers in some states are still composed of hereditary elements, of members appointed by the crown, or of members elected by a restricted suffrage. The governments of such countries are therefore in part at least aristocratic.

Democracy :-

Democracy has been variously conceived as both a political status, an ethical concept, and a social condition. Thus Giddings treats democracy as not only a form of government but also as a form of state, a form or condition of society, or a combination of all three. Some writers emphasize the distinction between political, economic (or industrial), and social democracy, and point out that the three things do not necessarily coincide in a given state.

Thus a people may be democratic, socially speaking, but may have at the same time an undemocratic government, or vice versa. But the normal condition is the coincidence of the three, that is, if society is democratic in its social and economic life, it will be democratic politically, on the other hand, if it is sharply differentiated into social classes, it is likely to have a government based, in part at least, upon recognition of special privileges of the upper classes.

Naturally, definitions of democracy as a form of government are multifarious, but like many definitions they are not exhaustive and do not admit of universal application. The ancient Greeks described democracy somewhat generally as government by the many.

Professor Seeley conceived it, in its modern sense, to mean

“a government in which every one has a share ”

a definition which would, if strictly interpreted, exclude from the category of democracy every existing government and every one which has been known in the past.

Dicey defined it as a form of government in which

” the governing body is a comparatively large fraction of the entire nation.

Lord Bryce, whose knowledge of the forms and workings of democratic governments was perhaps greater than that of any other modern writer, stated that

“the word democracy has been used ever since the time of Herodotus to denote that form of government in which the ruling power of a state is largely vested, not in any particular class or classes, but in the members of the community as a whole.”

He added, This means, in communities which tact by voting, that rule belongs to the majority, as no other method has been found for determining peaceably and legally what is to be declared the will of a community Which is not unanimous.

This definition of democracy as government by a majority of the people is perhaps as satisfactory as any that has been given, but, as Lord Bryce himself admitted, it would, if applied to certain states or communities which in fact exclude from the suffrage the illiterate and non-property owning or now taxpaying class, rule out states which certainly regard themselves as democratic.

Would it not also eliminate states in which women are still unenfranchised?

Formerly the exclusion of women from voting was not considered to be inconsistent with political democracy, but today when in many states women enjoy equal political privileges with men there is a large body of opinion in favor of the view that no state which denies them the right to vote, to sit in the legislature, and to hold office can justly claim to be considered as a true democracy.

Where one of the legislative chambers of a state is elected by universal suffrage but the other is entirely non-elective or is chosen by a very restricted suffrage, may the government be properly regarded as democratic ? Or if both chambers are democratically elected but the head of the state is a hereditary king, or if the constitution confers the right of suffrage on the mass of the people but the majority do not in fact exercise it, in consequence of their ignorance, or indifference, or are prevented by intimidation from exercising it, as is alleged to be the case in certain Latin-American republics, can it be said that the governments of such states are truly democratic?

Kinds of Democracy, the Pure Type :-

Democracies, like monarchies, are of several varieties. They are usually classified as

- Pure, or direct, and

- Representative, or indirect.

A pure democracy :-

so called, is one in which the will of the state is formulated or expressed directly and immediately through the people in mass meeting or primary assembly, rather than through the medium of delegates or representatives chosen to act for them. Manifestly, a pure democracy is, practicable only in small and relatively undeveloped Communities Where it is physically possible for the entire electorate to assemble in a given place and where the problems of government are few and simple.

In large and complex societies, where the mass of citizens is too numerous to be convoked in a common assembly, and where the legislative and administrative needs of the community are numerous and complex, such a system of government is, for physical and other reasons, impossible. In the city states of ancient Greece and Rome, pure democracy was not impracticable and it was not uncommon, but in the highly complex and larger states of to day it would, if attempted, break down in practice.

The only surviving examples of pure democracies to-day are found in four of the smaller cantons of Switzerland (Appenzell, Uri, Unterwalden, and Glarus) where the voters, since the Middle Ages, have been accustomed to meet in assembly (the Landesgemeinde) a sort of open air parliament for the purpose of electing their public officers, voting the taxes, and adopting legislative and administrative regulations.

Until 1948 the same system prevailed in the cantons of Zug and Schweiz, but with the growth of population and the increasing complexity of the problems of government and legislation it was abandoned and a representative system took its place.

In time it will probably disappear for the same reason in the remaining cantons where it now survives. The local town governments in some of the American states, notably those of New England, are sometimes cited as other examples of pure democracies. Formerly they functioned satisfactorily enough, but in the course of time new and changed conditions came into existence which have made the system less satisfactory.

In states or local communities where the referendum and initiative have been introduced on a large scale, a modified or limited form of pure democracy undoubtedly exists. In some such states to day it is possible for the people to initiate and adopt laws and constitutional amendments and determine questions of public policy directly themselves without the intervention or collaboration of representatives. In such communities the representative system is tending more and more to acquire the form of pure democracy although it will of course never be entirely or even largely superseded by the latter system.

Representative Democracy :-

The second type of democracy representative government as it is usually styled is that form in which the will of the state is formulated and expressed through the agency of a relatively small and select body of persons chosen by the people to act as their representatives.

It is base on the idea that while the people cannot be actually present in person at the seat of government they are considered to be present by proxy. Strictly speaking, a representative system of government need not necessarily be a democracy, if judged by modern standards, since the representatives may be chosen by a suffrage so restricted that it cannot be justly regarded as democratic nevertheless, if democracy be interpreted in a broad sense, representative government is at the same time a form of democracy.

Like the pure type of democracy, it attributes the ultimate source of authority to the people, but it differs from pure democracy in that it is constituted on the principle that the people are in capable of exercising in a satisfactory manner that authority directly themselves. In short, it rests upon the distinction between the possession of sovereignty and the exercise of it.

As to the origin of this now almost universal system of government, there has been much discussion and there is a wide difference of opinion. Some writers maintain that it had its. beginnings in ancient times, notably in Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and even in Hungary others, that the modern system

was merely a revival of the primitive Teutonic assembly of freemen. But the late Professor Henry J. Ford in his work on “Representative Government” (1924) concluded, after a careful study of the subject, that it hardly dates back to the middle of the nineteenth century.

Although it originated in England in the seventeenth century and gained a foothold in. Belgium in 1830 when parliamentary institutions were established, the general movement for representative government began abruptly, he says, in the year 1848 in France and Italy. Since then it has spread in one form or another until it has become, as stated above, very nearly universal.

Essentials of Representative Government :-

Strictly speaking, a representative government is one whose officials and agents are chosen by an electorate democratically constituted, Who during their tenure of power reflect the will of the electorate, and who are subject to an enforceable popular responsibility. According to this definition, a government by functionaries, whether legislative, executive, or judicial, who are appointed or selected by other processes than popular election, or who, if chosen by a democratically constituted electorate, do not in fact reflect the will of the majority of the electors or whose responsibility to the electorate is incapable of enforcement, is not truly representative. But judged by this rigorous test few, if any, existing governments could qualify as representative.

In many states the head of the executive branch of the government is not chosen by popular vote , in most of them the mass of executive and administrative officials, agents, and employees are selected by other methods than popular election , in the majority of them the judges of the courts are appointed by the executive or elected by the legislature. Popular usage considers a representative government to be one in which the legislative branch at least is popularly elected.

Thus in many of-the most representative systems of Europe (British, for example) there are, aside from the members of the parliament and local councils, no popuvlarly elected officials or agents at all. In all such countries the selection by executive or legislative appointment of the mass of administrative agents and judicial magistrates is not regarded as at all inconsistent with the principle of representative government.

Even in the United States and Switzerland,two of the most democratic republics, the principle of representative government is not understood to require the popular election of judges and administrative officials. Nor does it require the selection of even the members of legislative bodies by an unrestricted suffrage. As has already been pointed out, women were generally excluded from a share in the choice of all officials, legislative and otherwise, until very recently, and even now they are still excluded in a good many states which claim to have representative governments.

Similarly, in some countries which are recognized as classic examples of democracy, legislative representatives in one or both chambers are chosen by electorates from which large classes of adults are excluded. The truth is, as, Lord Bryce remarked, all governments are in fact aristocracies, in the sense that they are carried on by a relatively small number of persons.

This must necessarily be so. Representative government in the sense of government by functionaries all of whom are chosen by an unrestricted electorate, aside possibly from small and undeveloped communities, would be almost as impossible as the system of pure democracy itself.

Republican Government :-

The term “representative” government is often used as synonymous with “republican” government. Thus Madison in The Federalist defined a republican form of government as one in which there was a scheme of representation. It was, he said, a government which derives all, its powers, directly or indirectly, from the great body of the people and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, fora limited period, or during good behavior.

The two “great points of difference, ” said Madison, between a republic and a democracy (he was thinking of democracy in its pure form) are:

- First the governing power in a republic is delegated to a small number of citizens elected by the rest and,

- Second, a republic is capable of embracing a larger population and of extending over a wide area of territory than is a democracy.

In a democracy the people meet and exercise the government in person in a republic they assemble and administer it by their representative agents.

Madison rightly regarded hereditary tenures as inconsistent with modern notions of republican government, although he considered good behavior tenure for the judiciary at least admissible. It is also essential to the republican idea that the principle of representation shall be based upon a reasonably wide suffrage.

A suffrage so restricted, for example, as that which existed in France under the restored monarchy (1814-1830), when the number of voters did not exceed 300,000 out of a total population of about 30,000,000 or in Belgium before 1893, would hardly be considered consistent with republican government.

Republics have been classified as aristocratic and democratic as monocratic and plutocratic, unlimited, mixed, and limited , as corporate, oligarchic, aristocratic, and democratic as federal and confederate as centralized-and unitary as hereditary and elective, etc.

The term “republic” was formerly employed to describe certain forms of government which popular usage to-day would designate as monarchical or aristocratic.” Thus Sparta, Athens, Rome, Carthage, the United Netherlands, Venice, and Poland have

all been described by political writers as republics, though none of them possessed that full representative character which , we today consider to be the distinguishing mark of a republic. Rome, for example, was organized on a military basis, Venice was an oligarchy of hereditary nobles, Poland was a mixture of aristocracy and monarchy. France under the constitution of the year XII was styled a republic, though the chief of state bore the title and rank of emperor, and the crown was hereditary in the Napoleonic family.

Other Classifications :-

Montesquieu classified governments as republics, monarchies, and despotism’s. He defined a republican government as one in which the whole body or a part of, the people exercises supreme power a monarchy as one in which a single person governs by fixed and established laws a despotism as one in which a single person directs everything by his own will and caprice.

The principle underlying this classification is partly numbers and partly the spirit and character of the government. Woolsey classified governments as monarchies, aristocracies, democracies, and “compound states. ” Other writers recognize only two forms, namely, monarchies and republics, the latter comprehending both aristocracies and democracies.

The fault with most classifications of government is, as was said of the classifications of states, that they do not rest upon any consistent scientific principle which will serve as a basis for the differentiation of governments with respect to their fundamental characteristics.

No single classification can be of much value there must be as many classifications as there are points of view from which the government may be considered.

The classification of governments as monarchies, aristocracies, and democracies has little scientific or practical value. To describe a government as monarchical gives little idea as to its real character a many governments described as monarchical are in fact democrats, and the distinction between aristocracies and democracies is often shadowy and largely a matter of definition.

Such a classification would assign to the same category such widely different governments as those of Great Britain on the one hand, and the former governments of Russia, Turkey, Prussia, and Austria on the other, while it would put into different classes the democracies of Great Britain and the United States.

FAQ:

-

What are the main classifications of government?

Governments are generally classified as monarchies, aristocracies, democracies, and republics. -

What is the difference between a state and a government?

The state is a sovereign political entity, while the government is the organization through which the state exercises authority. -

What is a monarchy?

A monarchy is a government where supreme authority rests with a single ruler, either hereditary or elective, such as kings or emperors. -

What is an aristocracy?

Aristocracy is a government in which a relatively small, privileged class holds political power. -

What is the difference between pure and representative democracy?

Pure democracy involves direct citizen participation in governance, while representative democracy relies on elected officials acting on behalf of the people. -

Are republics and democracies the same?

Not exactly. A republic is a form of representative government with elected officials, while democracy emphasizes majority participation and political equality. -

Can a government fit into more than one classification?

Yes, many governments combine elements, such as constitutional monarchies with democratic institutions or republics with aristocratic features.